Cakewalk

The Cakewalk was a dance developed from the "Prize Walks" held in the late 19th century, generally at get-togethers on slave plantations in the Southern United States. Alternative names for the original form of the dance were "Chalkline-Walk", and the "Walk-Around".

History#

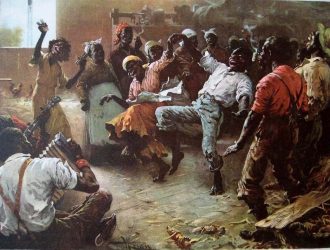

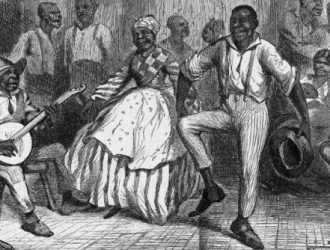

Originating in slavery and the plantation south, the Cakewalk was the sole organized and even condoned forum for servants to mock their masters. A send-up of the rich folks in the “Big House,” the Cakewalk mocked the aristocratic and grandiose mannerisms of southern high-society. Much bowing and bending were characteristic of the dance, which was more a performance than anything else. Couples lined up to form an aisle, down which each pair would take a turn at a high-stepping promenade through the others. In many instances, the Cakewalk was performance, and even competition. The dance would be held at the master’s house on the plantation and he would serve as judge. The dance’s name comes from the cake that would be awarded to the winning couple.

Carnival in full effect, the Cakewalk festivities turned convention on its head. The time of the dance was one in which typical order was set aside. Lowly slaves and servants were encouraged to mock the masters to whom obedience was mandated at all other times. The dancers donned fine clothes and adopted high-toned manners, and for the length of the performance they were not slaves but the stars of the show, their racial and social standing transcended.

As much as the Cakewalk managed to overcome these barriers temporarily, however, it reinforced them the rest of the time. Because the dance was generally sponsored and judged by the plantation owner, he became master of ceremonies, and became master of the joke as well. If the master is in on the jokes that mock him, then the jokes no longer harm his standing with the slaves. So it was with the Cakewalk, which further reinforced the master’s authority in allowing him to name a winner and thus make even his symbolic overthrow an attempt to appease him and an act of his decree.

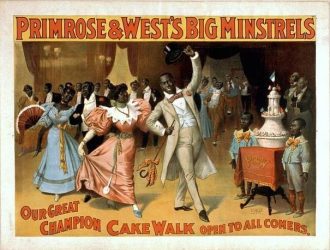

That the nation’s attention came to the Cakewalk is largely as a result of minstrel shows in the late nineteenth century. The dance’s exaggerated nature served perfectly for the physical, hammy humor of the stage shows, the participants generally played as goofy and bumbling as possible. The Cakewalk’s original meaning was lost; where it had originally been black slaves attempt to mock their superiors and for a minute live in autonomy, it had come to be the bumbling attempts of poor blacks to mimic the manners of whites. The dancers were no longer joking, but were portrayed as genuinely wanting to be like the superiors. This interpretation held great appeal in a nation where race relations were whites’ concerns about blacks were building steadily, and it became a way to briefly escape that tension. Again, dance had become a method of evasion and of escape, but now it was a tool for white the middle class to assure its social status and to ignore the spirit that gave rise to the Cakewalk in its first incarnation.

As a Plantation Dance#

The authors of “”Jazz Dance: The Story of American Vernacular Dance”” reported that an early 1950’s experiment with African guests turned up “no worthy African counterpart” to the Cakewalk.

First Person Accounts#

In the 1981 article “The Cake Walk: A Study in Stereotype and Reality,” Brooke Baldwin cites “an almost exhaustive compilation of those accounts which have been found so far”. This compilation consists of eyewitness accounts by ex-slaves from Virginia and Georgia recorded by WPA researchers in the 1930s, along with second hand accounts from other sources. Baldwin notes that “when the researchers of the Federal Writer’s Project of the WPA interviewed aged ex-slaves in the 1930s, there was no longer any need to suppress information about the happier moments of slave life.”

Louise Jones: “de music, de fiddles an’ de banjos, de Jews harp, an’ all dem other things. Sech dancin’ you never seen before. Slaves would set de flo’ in turns, an’ do de cakewalk mos’ all night.”

Georgia Baker said that she sang a song when she was a child. “Walk light ladies, De cake’s all dough.” She laughed and added, “Us didn’t know it when we was singin’ dat tune to us chillun dat when us growed up us would be cakewalkin’ to de same song”.

Estella Jones: “Cakewalkin was a lot of fun durin’ slavery time. Dey swep yards real clean and set benches for de party. Banjos wuz used for music makin’. De women’s wor long, ruffled dresses wid hoops in ’em and de mens had on high hats, long split-tailed coats, and some of em used walkin’ sticks. De couple dat danced best got a prize. Sometimes de slave owners come to dese parties ’cause dey enjoyed watchin’ de dance, and dey ‘cided who danced de best. Most parties durin’ slavery time, wuz give on Saturday night durin’ work sessions, but durin’ winter dey wuz give on most any night.”

Second Hand, Oral Tradition Accounts#

A South Carolinian told of Griffin, a fiddler who played for the dances of the whites as well as for the “annual cakewalks of his own people”. In 1960, a story told to him by his childhood nanny in 1901 was repeated by 80-year-old actor Leigh Whipple, “Us slave watched white folks’ parties where the guests danced a minuet and then paraded in a grand march, with the ladies and gentlemen going different ways and then meeting again, arm in arm, and marching down the center together. Then we’d do it too, but we used to mock ’em every step. Sometimes the white folks noticed it, but they seemed to like it; I guess they thought we couldn’t dance any better.”

Ex-ragtime entertainer Shepard Edmonds recounted, in 1950, memories related to him by his parents from Tennessee: “…the cake walk was originally a plantation dance, just a happy movement they did to the banjo music because they couldn’t stand still. It was generally on Sundays, when there was little work, that the slaves both young and old would dress up in hand-me-down finery to do a high-kicking, prancing walk-around. They did a take-off on the manners of the white folks in the “big house”, but their masters, who gathered around to watch the fun, missed the point. It’s supposed to be that the custom of a prize started with the master giving a cake to the couple that did the proudest movement.” Baldwin concludes that the Cakewalk was meant “to satirize the competing culture of supposedly ‘superior’ whites. Slaveholders were able to dismiss its threat in their own minds by considering it as a simple performance which existed for their own pleasure” (p. 211).

Tom Fletcher, who was born in 1873 and had a show business career beginning in 1888, wrote in 1954 that when he was a child, his grandparents told him about the Chalk-Line Walk/Cakewalk, but they did not know when it started. Fletcher’s grandfather told him, “your grandmother and I, we won all the prizes and were taken from plantation to plantation. The dance became a great fad. It took skill and good nerves…The plantation is where shows like yours first started, son.” Fletcher adds that the dance was called the “chalk like walk” and “There was no prancing, just a straight walk on a path made by turns and so forth, along which the dancers made their way with a pail of water on their heads. The couple that was the most erect and spilled the least water or no water at all was the winner.” He describes it being “revived with fancy steps by Charlie Johnson, a clever eccentric dancer” and becoming known as the Cakewalk.

“Cakewalk King” Charles E. Johnson related his grandmother’s recollections of a dance-walk from “the old days”. White guests would arrive by carriage to watch their slaves pair off and perform a dance-walk that was “as elegant and poised as a Mozart minuet“, but flavored with “an exaggerated grace that was sometimes comical”. Johnson relates that “The cadenced walking and high stepping was usually supplied by a violin, a drum and a horn of some kind. A towering, extra sweet coconut cake was the prize for the winning couple. The Cakewalk was still popular at the dances of ordinary folks after the Civil War.

Alternate Explanations#

Ethel L. Urlin, writing in the book “Dancing, Ancient and Modern (1912)”, stated that the Cakewalk “originated in Florida, where it is said that the Negroes borrowed the idea of it from the war dances of the Seminole…The negroes were present as spectators at these dances, which consisted of wild and hilarious jumping and gyrating, alternating with slow processions in which the dancers walked solemnly in couples. The idea grew, and style in walking came to be practised among the negroes as an art.”

“The Encyclopedia of Social Dancing” echoed the Seminole Indian connection, stating that “Classes sprang up among the negroes for the teaching of the dance and the proper way to promenade” in the 1880’s. As Florida developed into a winter resort, the dance became more performance oriented, and spread to Georgia, the Carolinas, Virginia, and finally New York.

Minstrelsy, Musicals, and a Popular Dance#

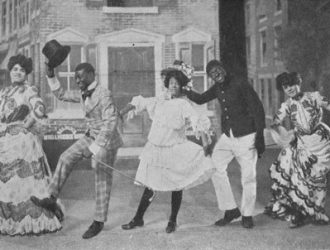

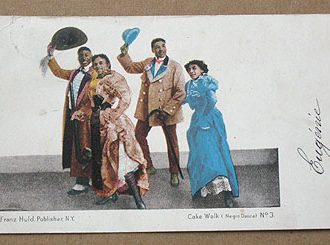

An exhibit at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial featured Blacks singing Folk songs and doing an old dance called the “Chalk-Line Walk” in a plantation like setting. The dance was “done in the original fashion”, as described by Fletcher. In 1877, performer-showmen Harrigan and Hart produced “Walking for Dat Cake, An Exquisite Picture of Negro Life and Customs” as a feature sketch at New York’s Theater Comique on lower Broadway. Thereafter, it was performed in minstrel shows, exclusively by men until the 1890’s. In the 1893, production of “The Creole Show”, which had opened in 1889, Dora Dean and her husband Charles E. Johnson made a hit dancing the Cakewalk, their speciality, as partners. During its run from 1889 through 1897, this show played to crowds in Boston and New York at the old Standard Theatre on Greeley Square, one of the first productions to discard blackface makeup. The production had a Negro cast with a chorus line of sixteen girls, and at a time when women on stage, and partner dancing on stage were something new. The inclusion of women in the cast “made possible all sorts of improvisations in the Walk, and the original was soon changed into a grotesque dance” which became very popular across the country.

A Grand Cakewalk was held in Madison Square Garden, the largest commercial venue in New York City, on February 17, 1892.

The Illustrated London News carried a report of a barn dance in Ashtabula, Ohio in 1897. Written by an English woman traveller, it stated, “The origin of that expression “taking the cake”, had previously been an enigma to me, if I had ever thought about it before, but it was suddenly in an unexpected and most practical way (revealed to me).” Just before the ball was declared finished, a long procession of couples was formed who walked in their very best manner around the room three times before the criticizing eyes of a dozen old people, who selected the best turned-out pair, and gravely presented them with a large plum cake.

In July 1898, the musical comedy “Clorindy”, or “The Origin of the Cake Walk” opened on Broadway in New York. Will Marion Cook wrote ragtime music for the show. Black dancers mingled with white cast members for the first instance of integration on stage in New York. Cook wrote, “My chorus sang like Russians, dancing meanwhile like Negroes, and Cakewalking like angels, black angels! When the last note was sounded, the audience stood and cheered for at least ten minutes. This was the finale which Witmark had said no one would listen to. It was pandemonium… But did that audience take offense at my rags and lack of conducting polish? Not so you could notice it!”

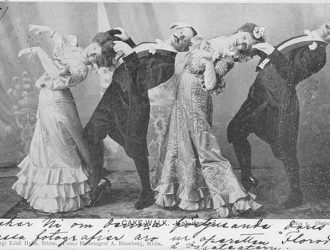

Performances of the “Cake Walk”, including a “Comedy Cake Walk” were filmed by the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company in 1903. Prancing steps were the main steps shown in the “Cake Walk” segment, which featured two couples, and a solo dancer. All dancers were African American. 1903 was the same year that both the Cakewalk and Ragtime music arrived in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Leaning far forward or far backward is associated with defiance in Kongo. “We are palm trees, bent forward, bent back, but we never break.” Another interpretations of these motions were “melting” to the beat, or protecting what is new (leaning forward) with the past (leaning back). The appearance of the Cakewalk in Buenos Aires may have influenced early styles of Tango.

“Cakewalk King” Charles E. Johnson, who, with his wife Dora Jean, achieved fame Cakewalking throughout the United States and Europe described his kind of dance as “simple, dignified and well-dressed”.

The Cakewalk was more fluid and imaginative than the established Two-Step, it was nevertheless a regularized form, more improvisational than its previous form, but highly formalized compared to later dances such as the Charleston, Black Bottom and Lindy Hop.

Modern Times#

The American English term “cakewalk” was used as early as 1863 to indicate something that is very easy or effortless, although this metaphor may refer to the carnival game of the same name in referring to the fact that the latter’s winners obtain their prize by doing no more than walking around in a circle. Though the dance itself could be physically demanding, it was generally considered a fun, recreational pastime. The phrase “takes the cake” also comes from this practice, as could “piece of cake.”

One version of the Cakewalk is sometimes taught, performed included in competitions within the Scottish-inspired Highland dance community, especially in the southern United States.

A version of the Cakewalk seen in vintage film clips from the early 1900’s is kept alive in the Lindy Hop community through performances by the Hot Shots and through Cakewalk classes held in conjunction with Lindy Hop classes and workshops.

Judy Garland performs a Cakewalk in the 1944 MGM musical, “Meet Me In St. Louis.”